La città dei Cento Campanili

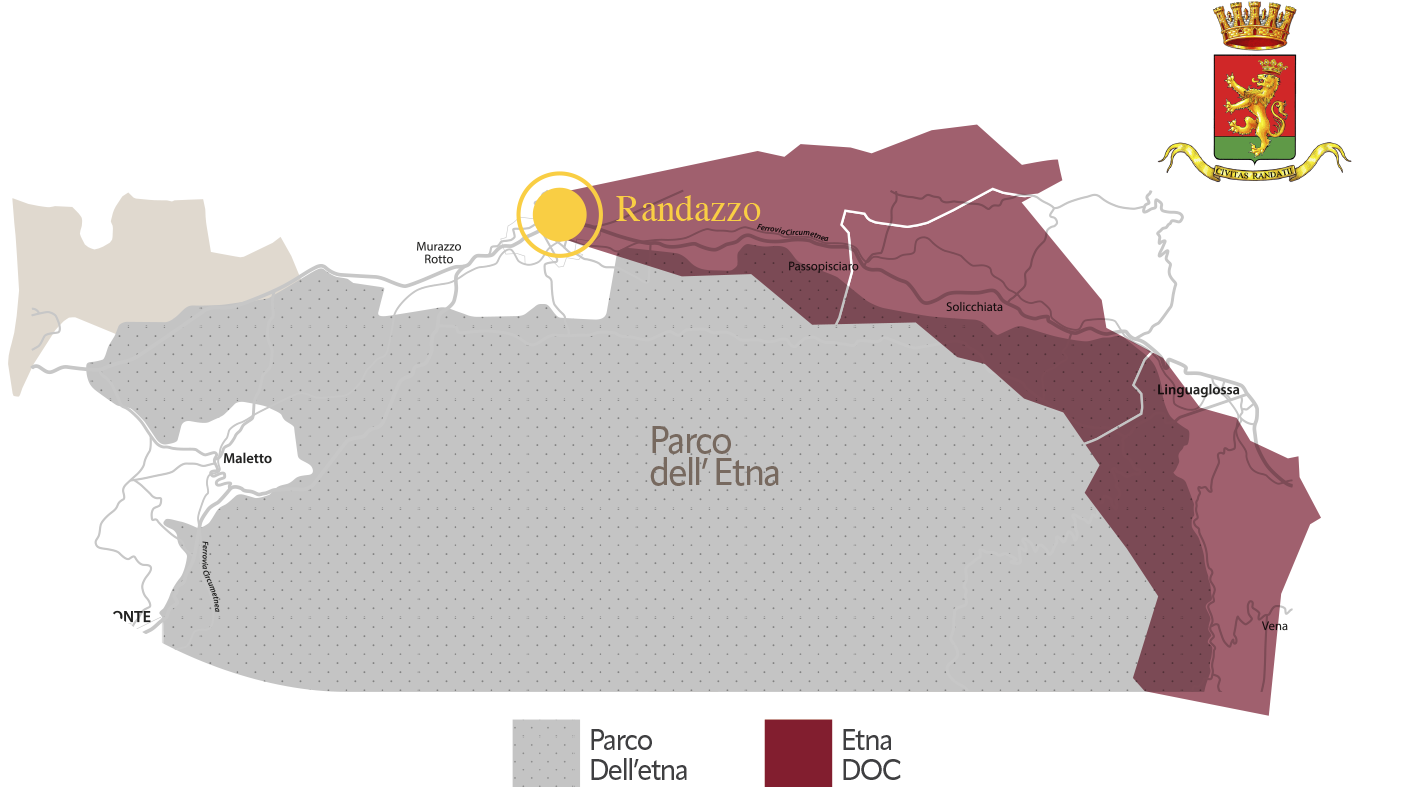

Randazzo is a charming village with a medieval allure, nestled on the northwestern slopes of Mount Etna. Its territory, along the Alcantara River, was already inhabited in prehistoric times, but it was the Greeks and Romans who transformed it into an important center, as evidenced by the archaeological finds discovered in a necropolis.

In the Middle Ages, under the Normans, Randazzo became a fortified stronghold with a city wall, part of which still exists today. The Normans, followed by the Swabians and the Aragonese, left deep cultural traces. Its urban fabric still reflects the ancient medieval division into three districts (Latin, Greek, and Lombard). Until 1492, Randazzo also hosted a substantial Jewish community, one of the most important in Sicily.

Gaetano Scarpignato

gaetanoscarpignato@gmail.com

And there is the sharp arch of the Eastern Gate – also called the Musto or Aragonese Gate – echoing with voices and the clatter of hooves: King Peter of Aragon plunges through it with part of his forces, while others remain outside the walls, in the field that, for centuries to come, will bear his name – Campo del Re (King’s Field)…”

Just these few lines from Federico De Roberto – excerpted from Randazzo and the Alcantara Valley (1909), his lyrical, detailed, and ever-relevant travel journal – are enough to capture the charm and illusion one can feel, rediscover, and experience while strolling through the streets and squares, alleyways and staircases of Randazzo. A town where ancient stones – of churches and palaces, arches and bell towers – whisper their stories.

Inside that “corner of the world that has survived the Middle Ages,” as De Roberto himself wrote, enchanted by the Etnean town where he stayed for several months. Because, as Mario Praz once said, for a place to leave an impression, it must be made of time as well as space – of history, culture, and the past.

And there it is – Randazzo, breathing with the long, living pulse of its stories, art, and myths. You can sense it in the 13th-century Church of Santa Maria, whose simple walls of black lava stone “have their own unique beauty and seem cast in bronze.” Or along Via degli Uffizi (now Via degli Archi), where pointed arches “open like a gallery” and delicate Gothic mullioned windows gaze over the street—the same street that Leonardo Sciascia photographed half a century later. Or in the Arab-Norman-Sicilian bell tower of San Martino, one of the oldest and most precious in Sicily.

And what of the 14th-century mansion on Via Agonia, with its stunning mullioned windows, like those that remain from the Royal Palace, once a favorite summer residence of kings and emperors? Or the 16th-century Palazzo Clarentano, a jewel of Gothic architecture, with windows divided by marble columns as slender as reeds? Or the 17th-century cloister of the former Convent of the Friars Minor Conventuals, now the Town Hall, with its rows of monolithic lava stone columns (similar to those in Santa Maria) and its elegant sequence of Serlian arches? And then, there’s the solemn marble statue of San Nicola, inside the church of the same name, sculpted by Antonello Gagini in 1522.

Not to mention the magnificent Transfiguration on the altar of the former Capuchin Convent’s church, a masterpiece by Giovanni Lanfranco, one of the most significant painters of the 17th century.

And then, the Vara – a breathtaking triumphal float, towering eighteen meters high and weighing several tons. Since the 16th century, every August 15, it has mesmerized onlookers as it is pulled by hand through Randazzo’s medieval heart. Upon it, around thirty children – aged six to thirteen, positioned at different heights, all the way up to the top -bring to life the Mysteries of the Dormition, the Assumption, and the Coronation of the Virgin, the city’s patron saint. The Vara never fails to move, to astonish.

Randazzo breathes with the weight of centuries, yet it invites visitors to step comfortably into its ancient and solemn mosaic of beauty and harmony—to awaken a vision that can become poetry.

Giuseppe Giglio

Main Sponsor